Part I. MIDGE

1

The Heir To Maunsleigh

“One apprehends.” said Mrs Cartwright majestically, “that the man is some sort of a cousin.”

There was a short pause.

“Indeed?” replied Mrs Burden weakly.

“Not, of course, a first cousin,” said Mrs Cartwright.

Miss Burden passed her the cake, looking wry. As much as a short, rather plump person of undistinguished appearance could. “Nevertheless one collects he is the legitimate heir, Mrs Cartwright?”

“What can you mean, my dear Miss Burden? Why, of course he is the heir!”

“Otherwise he wouldn’t be—wouldn’t be coming in for the title, Midge,” said Mrs Burden somewhat faintly to her dreadful sister-in-law.

Midge Burden gave her a dry look but said mildly enough: “True.”

Mrs Cartwright swallowed cake. “An excellent cake, my dear Mrs Burden, if just a trifle on the dry side. You must let me send you Cook’s receet: infallible. –Where was I?” No-one reminded her, but she went on: “Ah, yes. He has lived much in foreign parts.”

“Why?” asked Miss Burden baldly.

Mrs Burden gave her a look of anguished reproof but, perhaps fortunately, the majestic Mrs Cartwright neither noticed this nor perceived that Miss Burden’s replies to her conversational gambits were not entirely serious.

“Why? Well, I cannot tell you precisely why, Miss Burden, but one knows it is so.”

“Indeed? What sort of foreign parts, Mrs Cartwright?” asked Mrs Burden quickly.

Mrs Cartwright sipped tea, looking down her substantial nose as she did so. “India, one collects. –For years,” she added deeply.

The sisters-in-law could not see what was so dreadful in that. Lettice Burden avoided Midge’s eye. “India? How interesting,” she said feebly.

“Yes, indeed, Mamma! Mayhap he is a—a nabob!” said the junior Miss Burden excitedly.

“I thought he was an earl, Polly?” said her aunt in great confusion.

“Silly, Aunty Midge!” she gurgled. “He could have been a nabob in India!”

“One had not heard that he was a nabob, my dear,” admitted Mrs Cartwright on a regretful note.

“Oh, dear,” said the irrepressible elder Miss Burden.

“That is a pity,” agreed the innocent Polly.

Miss Burden opened her mouth again but caught her sister-in-law’s eye and thought better of it.

“And does he have a family, Mrs Cartwright?” pursued Mrs Burden valiantly.

Mrs Cartwright had not precisely heard. But she supposed he must do: for after all, he was an older man! –Polly’s round face fell.

“Older as in likely to have a family of horrible young hopefuls like my nephews?” asked Miss Burden, smiling at the mother of the nephews. “Or older as in the father of sons likely to afford the pretty young females of the district something to dance with?”

Polly’s face had brightened again. She looked eagerly at Mrs Cartwright.

Mrs Cartwright opined that Miss Burden’s latter supposition could well be the correct one, for the new earl was certainly not in the first blush of youth. She stayed for some time after that, though it gradually became clear that she had no further facts to impart. Nevertheless she, Mrs Burden and Polly enjoyed considerable speculation as to when the earl might take up residence, and whether he might grace the local dances with his presence—or whether, more likely, the younger ones of his family might—and whether he might give a Grand Ball at Maunsleigh—and so forth.

“Well, I hope you are duly enlightened!” said Miss Burden, as the visitor’s barouche clattered away to bring the news to the next lucky household of Lower Nettlefold.

“Midge, you are perfectly dreadful,” replied her sister-in-law, sinking onto her sofa with a sigh.

“I thought she was most restrained, for her!” said Polly with a loud giggle.

Miss Burden frankly grinned. “Yes, I was holding myself in for your sake, Letty.”

Lettice Burden sighed. “Well, thank you, my dear. But the strain of wondering whether you are going to continue to hold yourself in—!”

“I’m sorry,” said Midge, reddening. “But I find it hard to believe that the Mrs Cartwrights of the world have no sense of humour whatsoever: I find myself driven continually to test the theory for its validity.”

Mrs Burden smiled weakly.

“I think you can give up testing, in her case!” said Polly strongly.

“Yes, it is proven, is it not? I near to died when you said perhaps he was a nabob, Polly!”

Polly pinkened. “He could be!”

“Yes, why not?” said Midge cheerfully. “But the thing was, you see, I was biting my tongue not to say to Mrs C., Would one—sorry, one,” she said with great emphasis: Polly choked—“would one conceive of the passage from nabob to earl as an elevation, or not?”

“It must be an elevation in rank, Midgey,” said Mrs Burden in a shaking voice.

Polly gave a muffled snort.

“Thank goodness—you did not—say it!” squeaked Mrs Burden, suddenly breaking down in helpless giggles. In which she was immediately and ably joined by her daughter.

“No, but really!” said Midge, when they were over them. “She has found out he is an older man, not a first cousin—the which, by the by, the whole district has known forever—and has lived in foreign parts, putatively India. And that is all!”

“Almost certainly India,” said Mrs Burden unsteadily.

“Mamma, don’t set us off again,” warned Polly.

“No,” she said, blowing her nose. “Oh, dear! Well, it must be India, Midge, Mrs Cartwright did seem very sure.”

“Ah! But why did he go out there? ‘For years’,” she quoted deeply.

Mrs Burden and her daughter looked blank. Eventually Polly said: “To seek his fortune?”

“Well, yes,” owned Midge: “I suppose he could not guess just when his old cousin would pop off.”

“Midge!” protested her sister-in-law.

“Sorry,” she said with manifest untruth. “He might have blotted his copybook in his wild youth, of course, and been sent to foreign parts to—er—”

“Get him out of harm’s way,” finished Mrs Burden thoughtfully, nodding.

“Ooh!” squeaked Polly excitedly.

“Now look what you’ve done!” said Mrs Burden crossly to her sister-in-law.

“Er—mm. Sorry. –Polly,” she said impressively to her niece: “you are not to take it as gospel that the new earl blotted anything whatsoever in his early youth. Or at any time thereafter,” she added sternly, holding up an admonitory finger.

Polly collapsed in giggles again.

“You are too dreadful, Midge,” said Mrs Burden limply.

“Pooh!” Midge bent and kissed her sister-in-law’s still-pretty cheek gaily. “But do listen: all we have learned is that he was probably in India and is an older man.”

“Um—yes,” admitted Mrs Burden feebly.

“Mrs C. does not know,” said Midge, ticking the points off on her fingers, “whether he be married or no, whether he has a family or no, whether the family be old or young—in short, nothing! As to this talk of dances, it is highly unlikely that he will ever condescend to socialise in our obscure little neighbourhood, let alone hold a grand ball! Why, if we get an open day once a year out of him we may count ourselves lucky! And at that, it will be more than we ever got from the other man!” she reminded them roundly.

After a moment Mrs Burden admitted sadly: “That’s true enough.”

“But he was old and crotchety!” cried Polly crossly.

“Old, crotchety and an earl,” said Midge Burden drily. “Quite. Stop hoping. –Us peasant-folk,” she said in the accents of the country, achieving a horrible lop-sided leer and touching her forelock, “will just about be allowed to say ‘Good-day, yer Lardship’ as the wheels of his coach dash dust in our faces!”

“He could have five sons, all unmarried, and—and handsome!” cried Polly crossly. “How do you know he does not?”

“I will not say, And how do you know he does. But I will just say, Polly,” she said in a kinder tone: “that pleasant though it is to fantasize about the heir to Maunsleigh, realistically is it likely we shall ever do more than catch a glimpse of him going by in his carriage?”

“No,” admitted Polly wistfully.

Mrs Burden sighed. “No,” she agreed.

“Besides, I will wager you a whole sixpence that he has but the one son, who is forty if a day, very fat, and married with three hopeful heirs apparent!” said Midge with a smile.

“I have to admit, that is all too likely,” admitted Mrs Burden.

Polly counted on her fingers, frowning. “Not forty, Aunty Midge!”

“Thirty-five, then.”

“We-ell— But how old is the father, then?”

Midge shrugged. “What falls within Mrs Cartwright’s definition of an older man?”

No-one could say. Mrs Burden inclined dubiously to the opinion that since Mrs Cartwright was not young herself, she must mean at least—well, over forty-five. Say over fifty? Midge perceived in this estimate a certain optimism in the direction of unmarried grown-up sons, but said nothing. Polly thought he must be at least thirty-five. Though that—with a sigh—was old. Miss Burden was thirty. She eyed her tolerantly but agreed that it was not young.

“You did not truly have hopes, I trust, Letty?” she said somewhat uncertainly when Polly had run upstairs to put her bonnet on.

“Well, no, it would be silly,” said Mrs Burden with a sigh. “But it is so true that there are no young men in the neighbourhood!” She paused. “Our obscure little neighbourhood,” she murmured.

Midge smiled weakly. “Um, well, it is. And—well, Letty, dear, pretty as a picture though Polly is, an earl’s son, you know, even a younger son, will look higher than our little household for a wife.”

“I know,” she said sadly. “If only we could afford to give her a London Season, Midgey!”

Midge bit her lip. “Mm.”

Silence fell in the widowed Mrs Burden’s neat little parlour.

“He will be old, of course,” said Mrs Burden at last on a sour note.

Midge jumped. “What, the earl? Yes, of course he will be old, I am very sure that Mrs C.’s bad news, at the least, is always accurate!”

Mrs Burden smiled wanly. “It is not positively bad, dearest.”

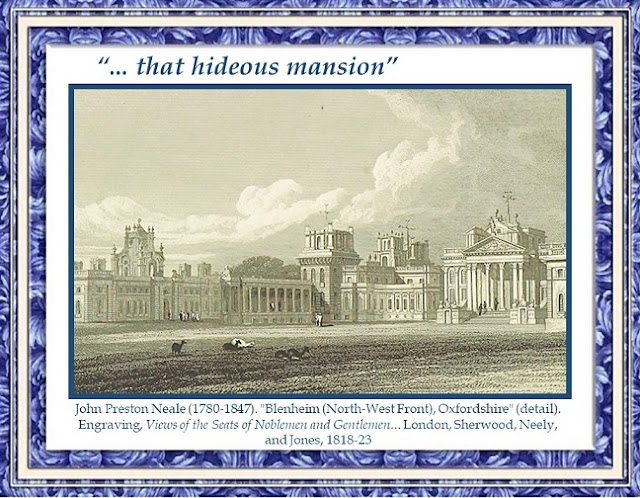

“Pooh, of course it is! For if he were, let us say, a sensible man of middle age, he would come to all the local hops and no sooner set eyes on the prettiest, best-natured chaperone in all the world than he would fall soundly in love with her and offer his heart and his earldom! And that hideous mansion,” she added by the by.

Mrs Burden had gone very pink. She gave a protesting laugh.

“You are much prettier than Polly: it is such a waste!” said Midge fiercely.

“Midge, dear! I am thirty-seven years of age!” she protested.

“Yes, and it is ten years since Will died, and it is high time some other decent man discovered your sterling worth!” she said crossly.

“Hush. Dear Will and I were very happy,” said Lettice softly. “I have put all that side of life behind me, Midge.”

“Well, you would not have to, if we were not condemned to live in this rural backwater! –I tell you what I should like to do, and that is hold this new earl to ransom until he agrees to marry you and make you a countess!”

“Ssh, Midge, you are talking wildly.”

“Yes. Well, it is as likely,” admitted Midge, suddenly glum, “as that the new earl will turn up at a Lower Nettlefold dance.”

“Yes, I fear that is so.”

“And I tell you what, Letty, it is Lombard Street to a China orange that he will be as yellow as a veritable Chinee! Well—years in India?”

Mrs Burden gulped. “In that case, I shall be very glad not to marry him!”

The eyes of the sisters-in-law met. They shrieked, and collapsed.

“Oh, dear!” gasped Mrs Burden at last, mopping her eyes. “How silly!”

“What is, Mamma?” asked Polly, appearing in the doorway with her bonnet on.

“Your aunt,” said Mrs Burden, mopping her eyes. “Hurry and put your bonnet on. Midge, if you intend to go walking.”

“Oh, it will only take me a second to put my bonnet on: I am not a belle like some!” said Midge with a laugh. She went over to the doorway but paused, and looked hard at Mrs Burden. Mrs Burden eyed her suspiciously.

Midge put a finger at the corner of each round eye and slanted them up horribly.

Poor Mrs Burden tried to control herself, gave a shriek, and collapsed in renewed hysterics.

“What?” cried Polly as her aunt vanished precipitately.

“Oh,” said her mother feebly, mopping her eyes, “it is just Midge.”

Polly nodded wisely. It usually was just Midge, in their little household.

The late Will Burden had been the son of obscure if respectable country gentlefolk. Having no other means of making a living, and being in any case an active young man, he had elected to go into the Army. It was now, as his sister had just indicated, ten years since he had been killed in the late conflict in the Peninsula. He had left a grieving widow, one seven-year-old daughter, three little boys, the youngest being but a baby, a small house on the outskirts of the village of Lower Nettlefold which had been an inheritance from an aunt, and a tiny annuity. And one unmarried sister, then aged but twenty summers.

Midge’s parents were both dead and she had been living in her brother’s house for some years. On his death any one of her three married sisters would have taken her, but Lettice Burden was only too well aware that in their households Midge would have become unpaid governess to the nephews and nieces and general drudge to the sister. So she had insisted Midge must remain with her. None of Will’s older sisters had raised very strong objections: Midge might in time have made herself useful to them, but it could not but be a nuisance being saddled with a girl of that age. And then, Midge’s was not a conciliatory nature. No, if Lattice wanted her she was, though the sisters did not phrase it quite so, even to themselves, welcome to her.

So Millicent Burden, dite “Midge” because a doating father had thought she was such a tiny midget of a thing, had found herself, aged twenty, thrown more or less into the rôle of mainstay and head of household to a little family. This had certainly not been by anyone’s design, least of all Lettice Burden’s. But Lettice at twenty-seven had been a broken, bewildered, lost thing without Will, and Midge’s had always been a strong and determined character.

Lettice had gradually recovered from the shock of her widowhood and begun to take an interest in her house and her children again and, ten years later, was as much herself again as was humanly possible to a gentle personality of great sensibility. She recognised herself that she would never have come through those dreadful years without dearest Midge. But she did not quite realise, for hers was not a mind much given to analysis, that Midge had spent her youth in the service of Will’s little family. Though she did recognise that it was a dreadful pity that circumstances had decreed there should be no pleasant young man in the district who might have understood Midge’s sterling qualities and—and appreciated her good points!

Midge’s good points might have been more apparent, at the age of turned thirty, had she not been pitchforked into the role of involuntary father at twenty; but this notion never occurred to the innocent Lettice. A certain tendency to dry humour had been somewhat accentuated in her by the necessity of cheering Letty up when she showed signs of sinking into a melancholy, cheering the children up over the continual small disappointments endemic to a household that had to watch every farthing, and just generally keeping cheerful during hard times.

Not to mention keeping cheerful in an environment which offered no social or intellectual stimulus. Will Burden had inherited his father’s small library: Midge had read every volume in it, even the sermons, half a dozen times by the time she was twenty-four. Sometimes she thought it was only that, that had kept her sane. Well, it was difficult to feel sorry for yourself when you compared your comfortable situation to that of Lear on a blasted heath or Hamlet discovering his uncle had murdered his father—and so forth! Midge Burden did not, however, compare her situation, either to its credit or its detriment, with that of Shakespeare’s famous lovers: she considered robustly that Romeo and Juliet were a great pair of gabies; and as to ever trusting themselves to that doddering old fool of a Friar Lawrence—! Lettice, who wept buckets over that play, could only smile limply at such declarations. Often the sisters-in-law read aloud from Papa’s volumes in the evenings until their candle guttered, but not Romeo and Juliet: Letty could not support the mocking way in which Midge read poor Romeo’s lines. Midge, on the other hand, was rather fond of The Taming of the Shrew, though declaring that she would not have knuckled under to him: but Letty thought that Petruchio was a horrid man; and so they did not share that play, either.

Lettice Burden was, as even those less biased than her sister-in-law admitted, a very pretty woman, if she was turned seven-and-thirty: tall, and very fair, with an elegant figure that had not spread with the advance of middle age but was still as graceful as ever. Her hair was delightfully abundant and curly, the eyes were big and blue, and the face oval and very sweet. And the cheeks as pink as they had ever been.

Polly was not as tall as her mamma, and her curls were more golden and her manner much more sprightly, where Mrs Burden tended to the quiet and composed—when she was not being overset by the irrepressible Midge. Polly was certainly very pretty: in fact by far the prettiest girl in the neighbourhood of Lower Nettlefold; but it was true enough that she was not as good-looking as her mamma: she had not the air of distinction that clung to Lettice Burden. But then, she was of course but seventeen, and liveliness and playful ways make up for most deficiencies, at seventeen. Her nature was as sweet and uncritical as her mother’s, but to her aunt’s regret she lacked Lettice’s intelligence: though she would listen with pleasure to some of the lighter volumes the ladies read in the evenings, anything much heavier than the delightful romps of Mr Sheridan would soon have her nodding in her chair. Midge and Lettice had never tried her with anything more recent: the late Mr Burden’s library did not include the oeuvre of such modernists as the author of Waverley or the shocking Lord Byron. The dawdling, limited life of Lower Nettlefold in fact suited Polly very well: or would have, if there had been but one pleasant young man to dance with!

But there was not: the closest the neighbourhood got to a pleasant young man was Mr Butterworth, the incumbent of the neighbouring parish of Upper Nettlefold: and he was all of two-and-thirty, so not precisely young, and very much the hunting-parson version, so not all that pleasant in his conversation, and very florid as to the cheeks and hairy as to the ears and nostrils, so not all that pleasant in his person, either, alas. Besides which, he very clearly admired Polly’s aunt! This was a cause of as much hilarity to Midge as it was to Polly: poor Mr Butterworth had not a hope, there. And Polly declared sternly that she would cut her aunt off without a shilling if she so much as dreamed of taking Mrs Cartwright’s advice and marrying the creature for the sake of, good Heavens, an establishment! Ugh, what a notion! Neither of the Miss Burdens, it may now be apparent, had yet been introduced to the enchanting works of the author of Pride and Prejudice, either.

Midge Burden was not even as tall as her niece: only about five foot two inches. Polly, a couple of inches taller, was wont to lament that she had not her mamma’s height, for the fashion was still for tall women, was it not? But Midge, who had a suspicion that whatever her height she could never have managed to be a fashionable lady, did not waste any time repining over what could not be mended. Though at times she reflected that being taller would be useful, in that it would enable one to reach more apples off the tree, or get Timmy’s ball out of the guttering without having to go two steps higher on the ladder than she cared to—and so forth. Not to say rescue Mischief from the ridge pole, the top of the gnarled old quince and even, on one dreadful day, Mr Lumley’s barn roof. Never had a kitten been more aptly named! Mischief was now a grandfather several times over and more than capable of getting himself down from any number of roofs, should he have been so silly as to go up there in the first place; but the name had stuck.

Midge, otherwise very unlike her late brother in looks, had inherited the striking, straight deep red hair that characterised the Burdens: Lettice did not know whether to be glad or sorry that her Polly had missed it, for it was certainly the most glorious colour: not a ginger at all, more a glowing mahogany: but then, with red hair, one did run the risk of freckles! Midge did not have freckles, she had the very clear, palest pinky-white skin that sometimes accompanies hair of that shade, and naturally pink cheeks. Her eyes, when not pulled up horribly at the corners in the imagined likeness of a yellow Chinee, were round and guileless and a limpid grey-green: a pretty enough shade, but not remarkable. The remarkable hair was quite unmanageable and quite unsuited to the frivolously curled fashions of the day that Polly’s golden ringlets fell into so naturally: Midge had long given up on curling rags and similar instruments of torture and just wore it braided in a coronet more or less on top of her head. Or just tucked up under her bonnet if she had rushed out in a hurry upon an errand.

The round, pink-cheeked face was quite pretty enough to have attracted the notice of any pleasant young man who might have happened upon her, but of course none had. Though it must be admitted that their former curate would have offered, back in the days before Midge had been upon the shelf; but Midge had not cared for Mr Mudgeley. Well, in the first instance there was the name, how could anyone seriously envisage being called “Midge Mudgeley” for the rest of her life? And in the second place, he was a swallower. Neither of these points might have counted for very much if he had been the sort of person who would have understood when Midge asked Mrs Cartwright blandly why the heir to Maunsleigh had lived in foreign parts: but he had not been. He had been entirely proper and serious-minded and not very bright. Nor had he been at all handsome: and it must be admitted that when she was seventeen Midge had fallen violently in love with a Captain Swann, a colleague of her brother’s: the most dashing creature imaginable, all black curls and flashing dark eyes. But he had not been very bright either and an older Midge did not at all regret that he had married another lady entirely.

No other candidates having presented themselves, Midge had never fallen in love with anyone else, except once, very briefly, five years since, with a gentleman glimpsed in Nettleford, the nearest big town: he had been merely crossing the road with his strong profile and straight back displayed to great advantage. Of course she never saw him again and, indeed, would have been entirely disconcerted had he spoken to her. And in spite of her undoubted competence in dealing with household accounts, temporary patches in the slate, childhood ailments, recalcitrant peddlers who came to the back door and would not go when Cook told them to, the vagaries of rosehip jelly, and candle grease in the good tablecloth, would not have known what to say to him.

Midge was happy enough in her restricted life in dull little Lower Nettlefold; but sometimes the gentle Lettice sighed, and reflected sadly that dearest Midge did not know what she was missing. And that it was all very well to laugh and say that marriage to a Mr Somerton did not appeal, for who wanted a husband with an uncertain temper and a paunch; and nor did marriage to a Mr Cartwright: goodness knew what he must have been like, but whatever it was, it clearly offered the risk of turning one into a Mrs Cartwright! But Midge did not know. That was not at all what Lettice and her dearest Will had had.

Midge did know, vaguely, or thought she had some sort of an idea; but after all she had never been a belle, she was too short and plump, if not precisely an antidote, and besides could not flatter a gentleman and talk to him in the way that gentlemen, however old, unhandsome, or dull, seemed to expect a young woman to talk to them—so what was the use of mooning over it? So Midge, very sensibly, did not. The heroes in Papa’s books were enough male company for her; at least they could not disappoint, for having read the tale once, one knew precisely what to expect of ’em!

The Burdens’ little household did not continue to speculate on the probable character, disposition, appearance and offspring of the heir to Maunsleigh after Mrs Cartwright’s visit that day, for as Midge pointed out, it was just so unlikely that they would ever set eyes on any of the family, except from a distance; and then, Lettice was not the sort of mother to encourage her seventeen-year-old daughter in unladylike speculations upon such topics as earls’ sons; but the rest of the district was not so reticent. High, low, and in between.

“These be what I call scrag-ends, Miss Humphreys,” warned Mrs Fred Watts, weighing wrinkled potatoes in her dim, fusty little shop.

“Yes, I suppose it is the season; our kitchen garden seems behind this year,” sighed Miss Humphreys.

“Ar,” agreed Mrs Fred, tipping the potatoes into Miss Humphreys’s basket before that lady could say she would rather have them in a paper. “It be the weather. My Fred, ’e says as ’ow it’s a soign!” She leered at her knowingly.

“A sign?” echoed Miss Humphreys feebly.

“A soign,” said Mrs Fred portentously, closing one protuberant and somewhat bloodshot blue eye significantly, “that all ain’t well ’ereabouts and that we’d best watch it with this new Lard a-comin’ to take over! Ar!”

“Oh—really, I do not think—well, it is just the weather, is it not?” said Miss Humphreys, very feebly indeed. Mrs Fred Watts’s was a powerful personality. Socially Miss Humphreys might have been far above her but Miss Humphreys knew all too well that in every other sphere of life she was far inferior to the robust shopkeeper.

“Ar,” said Mrs Fred mysteriously, shaking her head. “’Ens layin’, are they?”

“No,” confessed Miss Humphreys dully. “Though we have had a clutch of nice chickens.”

“If they don’t lay, Miss Humphreys,” said Mrs Fred, breathing heavily, as was her wont, on the initial H, “they’re only good for the pot! Now, a noice chicken broth, that’d do you and your poor brother and that Gertie Potts for ’alf the week, if so be as you could get that Gertie to stew it up good!”

“Yes. Thank you,” said Miss Humphreys faintly.

Mrs Fred beamed. “And if so be as your poor brother don’t wish to soil ’is ’ands, Miss Humphreys,”—Miss Humphreys blenched slightly at the onion-y blast from the H—“and understandable it be in a gent, I’m sure, my Jimmy’d be ’appy to do it.”

Jimmy Watts, aged fourteen, was notorious for the pleasure he took in wringing anybody’s chickens’ necks: Miss Humphreys did not doubt it. She managed a pale smile.

“But what I was sayin’,” said Mrs Fred, weighing out half a dozen eggs that Miss Humphreys had not asked for—Miss Humphreys watching this operation in a sort of frozen horror—“it be a soign. That Ned Munns from the Big ’Ouse, he were a-sayin’ as ’ow the new Lard, ’e ain’t never set foot in England this twenty year a-gone and more!”

“Er—I really fear that cannot be so, Mrs Fred,” said Miss Humphreys in a faint voice. “Lady Ventnor met him five years back, when he was visiting at Maunsleigh. On—on furlough, I think,” she added weakly. “Er—leave from the Army, you know. Of course he went straight back to India after that,” she finished very weakly indeed, under Mrs Fred’s protuberant blue eye.

“Ar. There you are, see? One swallow don’t make a summer.”

Miss Humphreys nodded obediently.

“And will a man what’s lived in furrin parts these last twenty year know the way things did oughter be done ’ere, that’s what I’m sayin’!” said Mrs Fred loudly.

“Oh, I see. Well, I suppose it will not much matter what sort of a man he be, for after all the master of Maunsleigh is a very great man, Mrs Fred: the agent will continue to manage the estates, no doubt.”

Mrs Fred sniffed. She wrapped the eggs carefully in a spotted handkerchief, Miss Humphreys watching this operation numbly. “She don’t never shop in the village!” she said on a vicious note.

“Who?” gasped Miss Humphreys.

“’Er. That Mrs Shelby. Thinks ’erself too grand for the loikes of us!”

“Oh, the agent’s wife,” said her customer feebly. “Ye-es... Well, I suppose their house is closer to Upper Nettlefold, Mrs Fred.”

“Huh! She don’t never shop there, neither! Only Nettleford be good enough for the loikes of ’er! –I knows it for a fact as her pa were naught but a tenant farmer over to Jefford Slough way, so what’s she got to give ’erself airs for? Mud and swamp it be round Jefford Slough, and the farmers’ brats with the tails out of their breeches!”

“Er—mm. It is certainly not such rich arable land as in our own little district.”

Mrs Fred snorted. “Ar! –’Ere,” she said, thrusting the kerchief-ful of eggs upon her.

... “So?” said Mr Humphreys with a twinkle in his mild blue eye as his sister returned from her shopping expedition.

Miss Humphreys swallowed. “Mrs Fred seems to fear that the fact that our kitchen garden is not doing well is a sign that—er—that the heir to Maunsleigh will do the neighbourhood no good.”

“I did not know that our humble little kitchen garden had such powers!” he marvelled.

“No,” she said weakly. “And—and she forced half a dozen speckledy eggs upon me, and would not accept payment.”

Mr Humphreys winced.

Miss Humphreys looked at him uncertainly. “You are not in pain, dear Powell?”

Powell Humphreys was more or less in continual pain: he could walk only with the aid of a crutch, and that very little: he had one leg shorter than the other, and suffered from a twisted back as well. He sighed faintly. “No. Well, only at the thought of being the object of the charity of Mrs Fred Watts.”

“She means well,” said Miss Humphreys limply.

“Quite.” After a minute he added: “Do I collect that the entirety of the local peasantry is damning the new Lord Sleyven before he has even set foot at Maunsleigh?”

“Very like,” she admitted faintly.

Mr Humphreys’s thin shoulders shook silently. “Poor—fellow!” he gasped.

“So you met him! But what is he like, dear Lady Ventnor?” gasped Mrs Cartwright.

Lady Ventnor was a plump, vague-mannered, vaguely good-natured lady whose position as the squire’s wife would have allowed her to do a considerable amount of good in the district had she but had the energy or the inclination for it. She was not, however, unpopular with her neighbours: her good nature led her to offer little dinners whenever she felt like it and quite regularly to invite the local ladies of any pretensions to gentility to take tea.

“Oh... Well, it was a very large gathering, of course. The dining hall at Maunsleigh is quite huge... I thought he seemed quite amiable.”

Had she not been a lady, Mrs Cartwright would have been reduced to a glare at this worse-than-useless report. “Indeed? Er—not above his company, then?”

Lady Ventnor ate a small cake, very slowly. “I would not absolutely say that.”

Mrs Cartwright watched in scarce-concealed impatience as her hostess thought it over.

“Cold. Yes, I would say. cold.”

Mrs Cartwright tried her not inconsiderable best, but that was the most she could get out of her.

“Mamma says,” reported Lacey Somerton. “that Mrs Cartwright’s latest is that he is a very unamiable man, much above his company.”

“Oh.” said Polly Burden, her face failing.

Lacey screwed her charming little lopsided face up hideously. She raised a non-existent quizzing glass and looked six inches to her best friend’s right. “Tolerable,” she groaned.

Polly gave a shriek, and collapsed.

“—In any event,” concluded Lacey when the friends were over it, “he is positively elderly, so who gives a fig?”

“Oh, a very good sort of man!” said Sir William Ventnor heartily. “Very good seat on a horse!”

The squire was also the M.F.H. And took his responsibilities in that area very seriously. Anyone who had a good seat on a horse was accepted by him without question as a very good sort of man. The Reverend Mr Waldgrave eyed him tolerantly. “Mm.”

... “Well?” said Mrs Waldgrave impatiently, ere her husband’s cloak was scarce off his back.

Mr Waldgrave eyed her sardonically. “A very good sort of man. Very good seat on a horse.”

“Septimus, he cannot have said that! Why, he said it of that dreadful Mr Newbiggin from Nettleford!”

“Newbiggin is not necessarily dreadful merely because he has amassed a considerable fortune in trade, my dear.” he said mildly.

“Rubbish, Septimus, you know very well what I mean! Even Sir William cannot have said that of the new Lord Sleyven!”

“I assure you that he did.”

“Well, what else did he say?”

The Reverend Septimus Waldgrave suppressed a sigh. “Nothing. He has no powers of description. I did warn you, my love.”

“No powers of description?’ He has virtually no powers of rational thought!” she said angrily.

“Hush, Marina, that is not a suitable thing to say of Sir William.”

“The living is not in his gift, but in this new Lord Sleyven’s, may I remind you. Septimus,” she said grimly.

The incumbent of Lower Nettlefold replied tranquilly: “True.”

“Well—well, did he say if he be old or young?” she demanded desperately.

The Waldgraves had three unmarried daughters, all of whom been out upon the world for some time.

“Disabuse yourself of the notion that a Wynton of Maunsleigh will look in a country vicarage for a wife, my love.”

“I am sure a Waldgrave is as good as anyone! And recollect, my dear Mamma was a Gratton-Gordon! –And who are the Wyntons, pray? The title is no later than Queen Anne!”

This was true: the Wynton of the time had campaigned with Marlborough. And been rewarded in the usual way. Subsequent judicious marriages had brought the family considerable wealth. True, Mrs Waldgrave was not above reminding her husband that one of the marriages had been with the daughter of a wealthy tradesman.

The Reverend Septimus sighed. He had warned her.

“You had best watch out, Mr Potts,” said Midge with a twinkle in her eye. “With this new Earl of Sleyven in the offing, won’t the gamekeepers be particularly on their toes?”

“Ar!” replied Mr Potts, laying a finger to his unlovely bulbous nose. “They gotta catch me, first!”

“That’s what I mean: watch out,” she said baldly.

Mr Potts cackled. “Them! A-polishin’ of their guns and leathers, that be about all them’s fit for! I said to my boy, Jem, if that arse-’ole of a Tom Watts—beggin’ your pardon, Missy—if ’e gets ten pheasant chicks outa them clutches this year, it’ll be more’n ’e deserves! Ar! –Draughts, is what, Missy.”

“I see. That doesn’t sound too good.”

Mr Potts spat. “Newfangled.”

“Yes. Um—the new coops are to impress the new earl, is that right?”

Mr Potts spat again. “Ar. –Well, do you want this ’ere bunny, or not?”

Midge gave a smothered giggle: the “bunny” was a good-sized hare. “On the understanding that we shall both be transported if we’re caught, Mr Potts: yes!”

Cackling, Mr Potts laid the hare in her basket, laid Midge’s old shawl tenderly over it, laid a bunch of radishes on top of that, and accepted the usual remuneration.

“I suppose you haven’t heard what sort of a man the new Lord is, have you, Mr Potts?” asked Midge, preparing to depart.

Mr Potts scratched his unshaven chin. “Not in pertickler. But tell you one thing, none of these ’ere lards be no good to the common people, Missy, and you may lay yer loife on it!”

Inasmuch as transportation was frequently for life and frequently resulted in death whether or no it were for life, and inasmuch as it was the preferred punishment for the taking of game, even when the said game came into a poor man’s garden and destroyed the crops that were to have fed his family, Miss Burden could not but concede he had a point. She shook hands very firmly with the somewhat startled Mr Potts, and departed, looking grim.

“Ar,” said Mr Potts to himself, gazing after the crumpled print gown. “Pity as more of gentry ain’t more like ’er.” He thought on it some more. “Good bum on ’er, too,” he concluded, hitching at his crotch. “Ar!”

Mrs Newbiggin had, Mrs Waldgrave was to feel when it was reported to her, inveigled the three Miss Waldgraves into her flashy new barouche—a vehicle quite unsuited to her position in life.

“Go on, me dearies, guess!” she urged, the three chins wobbling around the blue and white stripes of the most unsuitable ribbon on the most unsuitable bonnet.

“Mrs Cartwright told Mamma he must be at least forty-five,” ventured Miss Portia. Miss Waldgrave gave her a minatory look, but did not utter a reproof, in front of Mrs Newbiggin.

“No!” said Mrs Newbiggin triumphantly. She shook all over with fat chuckles. “But you’re gettin’ warm, me deary! Try again!”

Miss Amanda Waldgrave ceased trying to see if that back that disappeared around that corner really had been Mr Shaw and ventured: “May I venture a guess, ma’am? Sixty?”

“Colder!” said Mrs Newbiggin triumphantly.

“Pray tell us, Mrs Newbiggin,” said Miss Waldgrave politely.

“Well, I will, acos these is a-wandering all over the shop!” she said, laughing. “Fifty! There! He’s a man of fifty, me dears, true as I sit here, and I had it off Mrs Shelby herself!”

“She will have met him, I collect?” said Miss Waldgrave coldly.

The coldness passed the good-natured Mrs Newbiggin by. “Lord, no, bless you, Miss Waldgrave, she ain’t never laid eyes on ’im in ’er puff! No, but Mr Shelby knows, out of course. Now, where can I drop you young ladies? Or stay, it looks like it be a-goin’ to rain: you can’t possibly get yourselves all the way back to Lower Nettlefold on a day like this! Let me take you on your errand and then drive you home, me dearies!”

“No, I thank you, Mrs Newbiggin, we are being collected, later,” said Miss Waldgrave firmly. “I should be grateful if you would drop us at Miss Bright’s, the milliner’s.”

Sadly the genial Mrs Newbiggin dropped them at Miss Bright’s. Well, there weren’t much to any of the three of ’em, but they were youngish, and apart from Miss Waldgrave, merry enough little things, and her and her Percy never had had any girls of their own. Not but what— Well, encouragin’ of ’em wouldn’t do, for that Miss Amanda, she was quite pretty when she forgot her airs and graces. and their eldest boy, Ted, was intended for the mayor’s second daughter, his Worship being a very warm man indeed, and then, Percy had his eye on a likely lass for Benny, their second. And ladies was all very well, but not a penny to share between ’em? And did any one of ’em know how to keep household?

Mrs Newbiggin drove off, comforting herself with these reflections.

In the Burdens’ front parlour Polly counted on her fingers. “It is possible.”

“Fifty?” cried Lacey Somerton in tones of revulsion.

Amanda Waldgrave agreed with a shudder: “One absolutely could not, Polly, my dear!”

“Not him,” said Polly, reddening. “I mean, if he is a man of fifty, then—then very probably he may have a family of—well, say he married in his early twenties...”

“Oh, gracious!” cried Lacey. “Yes! One for each of each of us! And for your sisters, of course, dear Amanda,” she added hurriedly.

Amanda counted slowly on her fingers. “I fear he would have had to marry at twenty, or even less... I mean, Eugenia is turned twenty-seven.”

“One each for you and Portia, then!” said Lacey with a loud giggle. “Now, who shall have the heir? I think we should award him to you, Polly: you are by far the prettiest!”

Polly protested, giggling, but was overborne.

... “Help,” she said from the window as Amanda, waving, went on her way

Lacey was perched on a low pouffe much favoured by Midge, looking into the book Midge had left upon it. “Horrors, your Aunty Midge must be a real bluestocking, Polly!”

“Yes, she is, I suppose,” she agreed. “Well, at her age, it cannot signify.”

“What were you saying?” said Lacey, laying down the book with a shudder.

“Oh—just that the earl’s son who is to be awarded Amanda Waldgrave will have to be very, very fond of bows!” she hissed.—Lacey screwed up her face, and nodded wildly.—“I counted fifteen today!” hissed Polly. “Not even including the ones upon the bonnet!”

Lacey collapsed in splutters.

Polly pointed to her left wrist. “One.”

Lacey shook helplessly.

“Two,” continued Polly, pointing to her left elbow.

“Stop!” she squealed.

“Three,” said Polly relentlessly, indicating the mid-point between left elbow and left shoulder. The finger moved up towards the shoulder. “F—”

“Stop!” wailed Lacey

Abruptly Polly gave in and also collapsed in giggles.

“I have it on excellent authority.” said Mrs Cartwright in a very firm voice, “that he is a man of fifty, with a hopeful family. Five sons.”

“One for each of the Waldgraves, so I suppose that leaves one each for Polly and Miss Somerton,” said Midge dubiously. “Unless they are still in short coats.”

“You will have your joke, Miss Burden, but I can assure you that they are not. And as for the Waldgraves!” Mrs Cartwright allowed herself a slight titter: still, however, remaining awesomely majestic.

“Mrs Waldgrave’s mamma was a Gratton-Gordon,” Midge reminded her, straight-faced.

At this Lettice stared grimly at Mrs Cartwright’s hideous clock on Mrs Cartwright’s hideous green marble mantel.

“I—I am almost sure that Mrs Shelby said the Earl was not a married gentleman,” faltered Miss Humphreys.

Mrs Cartwright gave her a not unkindly look down her large nose. “You mistake, my dear.”

Midge swung happily down a country lane, her patched parasol slung over her shoulder in a carefree manner that did nothing to shield her face. There was a clatter of hooves and carriage wheels behind her: she ducked hurriedly to the side of the lane.

The barouche drew alongside. It slowed. “Miss Burden, is it not? Good-day.”

“Good-day, Mrs Shelby. How are you?” called Midge happily, smiling at her. The Maunsleigh agent’s wife was reputed locally, without approval, to keep herself to herself. With neighbours such as Mrs Cartwright, Miss Burden personally had never found it in her heart to blame her.

Mrs Shelby visibly hesitated. “I am going towards Maunsleigh. May I offer you a ride?”

“Thank you. That would be lovely: if you could drop me near the main gates, I’ll walk home: it’s been an age since I was over that way. The round trip is a bit much, really.”

“Of course. Pray get in,” said Mrs Shelby with extreme politeness.

Midge got in, smiling her unaffected smile at the agent’s wife. After a moment, since Mrs Shelby seemed at a loss for words, she said: “What a truly wonderful wrap that is, Mrs Shelby! –Is it a wrap? I’m not very good at fashions, I’m afraid!”

“Er—a matching pelisse and wrap, Miss Burden,” said Mrs Shelby, eyeing her dubiously.

“Lovely!” said Midge with a sigh of simple admiration.

“It is a heavy silk,” offered Mrs Shelby in a careless voice.

“I see! That bronze is a charming shade. And that is a delightful fur edging. Much prettier than Mrs Somerton’s fur wrap. Hers is lapin; what is yours?” asked Midge with interest.

Mrs Shelby allowed herself to stroke the wide band of fur which edged the stole that matched the charming pelisse. “As a matter of fact, it is fox, Miss Burden.”

“I do so like it.”

“Thank you. –I am going to call on Mrs Fendlesham,” revealed Mrs Shelby abruptly.

“Oh, the housekeeper at Maunsleigh? That sounds pleasant. I expect she will offer you the most wonderful nuncheon with the tea-tray.”

“Er—well, yes, it is always delightful to take tea at Maunsleigh, of course.”

“Have you ever seen the pictures?” asked Midge on a wistful note.

“Certainly. Mrs Fendlesham has several times shown me the house.”

“Lucky you,” said Midge with frank envy.

Mrs Shelby smiled a little. “It is very fine, of course. But the distance from the kitchen to the dining-room is quite unbelievable! Were I the hostess, I should spend my time agonising that the food was going to be cold by the time it reached the table.”

Midge was unaffectedly intrigued by this insight into the behind-the-scenes life of the great house, and urged Mrs Shelby to tell her more. Which the agent’s wife, unbending from her former rather stiff manner, did. They were trotting along a much improved road surface beside the great stone wall that bordered the grounds of Maunsleigh when she volunteered: “Mr Shelby expects his Lordship presently, you know.”

“Indeed? We keep hearing rumours,” said Midge with a twinkle, “but all of them contradictory, and some of them quite extraordinary, so I have discounted the lot!”

“Yes,” said Mrs Shelby, faint but pursuing. “I have never met Colonel Wynton—Lord Sleyven, I should say, of course—but Mr Shelby assures me he is the sort of man who will not fail to do everything that is expected of him.”

There was a short silence.

“I see,” said Midge thoughtfully.

Mrs Shelby looked at her doubtfully and gave a nervous laugh. “That is—is all that one could hope for, I think?”

“Well,” said Midge slowly, “not all that one could hope for. In some ways, it’s a lot more than could have been hoped for. But in other ways, Mrs Shelby, if your husband really said that, I think he has managed perfectly to damn the man with faint praise!”

Mrs Shelby went very red.

“I do beg your pardon,” said Midge instantly. “Of course I did not mean at all to criticise your husband’s attitude towards his new employer. Pray forgive me.”

“No,” she said, licking her lips. “Oh, dear! I mean, of course, yes, Miss Burden— I mean, there is nothing to forgive! Kenneth says he is the coldest man he ever met!” she burst out. “He could not tell if he approved of what had been done on the estates these last few years or— Oh, dear!”

Midge leaned forward and laid her little warm hand gently on the over-smart one encased in tight lavender kid that was plucking nervously at the skirt of the modish pelisse. “Don’t. I won’t breathe a word, I promise.”

“Thank you,” said Mrs Shelby, with tears in her rather cold little eyes. Suddenly she told Midge a lot about Kenneth’s weak digestion that she frankly would rather not have known.

“I know I may rely on your discretion, my dear Miss Burden,” she said, suddenly stiff again, as they drew up at the imposing main gates of Maunsleigh.

Midge could see that the wretched woman was regretting having let herself go. “Of course,” she said calmly, getting out. “Thank you so much for the ride.”

“Not at all, Miss Burden. Good-day,” said Mrs Shelby stiffly.

“Good-day, Mrs Shelby,” replied Midge, doing her best to smile.

Mrs Shelby bowed slightly and ordered her coachman to drive on. The gates were heaved open by the gatekeeper and the barouche drove through.

Midge walked slowly back the way they had come, shaking her head.

“Now, this will please you ladies!” beamed Mr Butterworth.

Lacey Somerton looked helplessly at the black hair curling from his nostrils. “Yes,” she said faintly.

“Sit up straight, my dear,” commanded Mrs Somerton. “What were you saying, my dear Mr Butterworth?” She smiled graciously at him: he was, of course, the only unattached gentleman in the neighbourhood between the ages of seventeen and forty. Apart from poor Mr Humphreys.

“I was saying that I have heard some news of developments at Maunsleigh, Mrs Somerton.” Mr Butterworth bared his large teeth at her.

“Are the family moving in, sir?” asked Polly Burden politely, wishing she had not chosen today to call on Lacey. And trying not to look at his nostrils. Or his ears.

“The Earl is due very soon, yes. I had not heard there was a family, my dear Miss Burden,” he said in a puzzled voice.

“Oh.”

“Indeed, no more had I,” agreed Mrs Somerton smoothly. Her daughter gaped at her. “Lacey, my dear, pray pass Mr Butterworth the watercress sandwiches!”

Jumping, Lacey passed the sandwiches.

Mr Butterworth did not care for cress sandwiches but he took one. “I had it from Shelby himself—a very good sort of man indeed.”

“Oh, quite,” said Mrs Somerton without interest. Mr Shelby was a married man whose sons were still in the nursery.

“The Earl,” said Mr Butterworth, smiling ingratiatingly at the ladies, “is said to be a man of fifty, very amiable in his manner, and a bachelor.”

There was a stunned silence—despite Mrs Somerton’s disclaimer in the matter of families.

“To summarize,” Midge summed up coldly, from her commanding position on the hearthrug: “we have learned that he is a bachelor of fifty or possibly thirty-five with five sons of marriageable age and a distinguished career in the Indian Army—that or completely unknown to the Indian Army—and either a bruising rider to hounds, or not.”

The three young ladies glared at Miss Burden resentfully.

“I think we had best give it up and get on with the Italian lesson,” she concluded. “Unless you young ladies feel capable of discussing earls and earldoms and the subject of inheritance in Italian?”

Very red and pouty, Polly, Lacey and Amanda admitted they did not feel so capable, and got on with the Italian as originally planned.

“Good morning, Mr Humphreys,” said Midge with a smile. “If may, I should like to borrow a book that does not mention a single earl or unmarried son.”

Powell Humphreys replied, unmoved: “I think I can promise there is nothing on my shelves that does so. How is the Latin?”

“Not improved, I fear,” she admitted with a sigh.

“You’re not working at it,” he murmured.

“How true! And do you know why?” said Midge wildly. “It’s because I’m spending all my time listening to ignorant prattling about possible earls and putative earls’ sons, and—”

“Hush!” he said with a laugh. “Try some Petrarch: very soothing.”

Midge took the book but looked at him warily.

“What is it?” he said.

“This isn’t going to lead imperceptibly on to a suggestion that I try Horace, is it?”

“Well—”

She put the Petrarch back.

Sighing, Powell Humphreys said: “Take the Petrarch, Miss Burden: I promise you I will not use it as a pretext to inflict Horace upon you. –You’d like him,” he murmured.

Midge took the Petrarch and went over to the door. “Too hard,” she said definitely.

“But that leaves me with no-one in the whole village with whom I may discuss Horace,” he said plaintively.

“Try Mr Waldgrave: he must have done Latin in order to achieve Orders.”

“What a very hard-hearted woman you are,” he said sadly.

Midge gave a delighted gurgle.

“No, wait!” he said, as she opened the door. Midge waited, looking wary. “I have it: of course! The new Lord Sleyven will prove to be an entirely literate man with whom—”

Miss Burden gave a loud groan and rushed out.

“—with whom I may discuss Horace!” he finished loudly with a laugh.

There was an answering laugh from the passage: he heard the front door open and close and her footsteps patter down the path.

Powell Humphreys sighed and looked at the space in his bookshelves where the Petrarch had been. “Yes,” he said vaguely to himself.

“’E’s a-come!” reported Mrs Fred Watts importantly.

“Really?” said Lettice on a weak note.

“Who’s seen him, Mrs Fred?” asked Midge briskly.

Mrs Fred cut a huge hunk off the flitch of bacon. “This’ll do yer nicely to yer suppers, Mrs Burden,” she announced. “Moy Fred’s seen ’im, that’s ’oo, Miss Burden.”

“That proves it!” conceded Midge, smiling at her.

Mrs Fred sniffed slightly, but nodded. “Seat on a ’orse loike what the old Lard—not the last man, ’is father, I mean—loike what ’e ’ad, moy Fred reckons.”

“Mrs Fred, I thought the previous earl died at the turn of the century?” said Lettice feebly.

“Twenty year agone and more, aye. Well, Fred can remember back that far!”

“Yes, but was he not very elderly?”

“Seventy if a day! Oh, I see what yer a-thinkin’, Mrs Burden. No, got out on a ’orse till practically ’is last breath, ’e did. Straight back to ’im loike what you never saw.”

Suddenly Midge went very pink. She went over to the door of the little shop and stared out into the street.

“Er—well, I wonder if it will make very much difference to us what the Earl may be like?” said Lettice on a weak note, wondering what the matter was.

Mrs Fred winked. “Don’t suppose it will, Mrs Burden, no! –’Ere!”

“Mrs Fred, we really do not need bacon this week,” said Lettice, trying to be firm.

“Ain’t killed yer pig, ’ave yer?”

“No: the boys have named it Ronald and made a pet out of it, the creature’s going to live until it’s ninety!” confided Lettice with a laugh.

“Don’t you pay ’em no heed! Ronald, hey?” said Mrs Fred, shaking all over. “Well, ’ere, take it. –Yer don’t owe me nothin’.”

“We cannot take all this bacon for nothing,” said Lettice firmly.

“Then take it for that little dress what Miss Burden made moy Lily’s Vera!” said Mrs Fred loudly, going very red.

“Oh,” said Mrs Burden with a smile. “I see. In that case, thank you, Mrs Fred, we should be glad of it.”

“Ar. –And tell you what, troy up to Seven Acre Field, if you wants good mushrooms!” she hissed.

Midge came back to the little counter. “Good, we shall. Thank you, Mrs Fred.”

“What was it, dearest?” asked Lettice as they emerged onto the village street again.

“Oh—nothing,” said Midge lamely. “It’s so silly... Well, I never told you, but once when I was in Nettleford I saw a—a gentleman—at least, I suppose he was. A man, at any rate.”

“Yes?” said Mrs Burden, very puzzled.

“Um, what Mrs Fred said just then about the late Lord Sleyven’s father and—and this man’s seat on a horse— It’s so stupid!” she said, going very red. “It just suddenly brought it back to me.”

“Oh. Who was he, dearest?”

“That’s just it! I’ve no idea!” said Midge desperately. “It was just a glimpse, and—” She broke off, biting her lip.

“I see!” said Lettice with a little laugh. She took her hand gently and squeezed it. “Well, I’m very glad to learn that you’re not immune!”

Midge smiled weakly. “No.”

Lettice walked on with her, smiling a little; but after a while she found herself reflecting that it was a great pity that Midge’s fancy could not alight on something rather less like a belted earl and the heir to Maunsleigh, and rather nearer to everyday life.

Next chapter:

https://thepatchworkparasol.blogspot.com/2022/12/country-diversions.html