3

Vanitas Vanitatum

“Portia Waldgrave is to wear palest yellow gauze, and Amanda will be in blue muslin over a white satin underdress, and even Miss Waldgrave is to have a new gown: lilac sarsenet!” reported Polly, scowling horribly at her aunt.

“She is at an age to support it,” agreed Miss Burden calmly.

“Aunty Midge!”

Midge sighed. “These new gowns are in addition to the new gowns they had for the al fresco breakfast, I collect?”

“Of course!” she said impatiently. “Those were morning gowns!”

“The Earl of Sleyven is costing the county a fortune: I suppose it is too much to hope that he will put a fortune, even a small one, back into it,” said Miss Burden on a dry note.

Polly looked blank. “What do you mean?”

“I think I mean, to mention one point only, those dreadful slums over Jefford Slough way. –The tied cottages,” she said clearly.

“Oh,” said Polly blankly.

“The workhouse could do with a new roof, too.”

“Oh. Um—is that not the responsibility of the parish?” she said vaguely.

Miss Burden took a deep breath. “Very like. The parish, however, as you may not have remarked, is poor. –And becoming poorer by the day, with all this money its inhabitants are throwing away on new gowns and new bonnets! Oh, and in the case of the Miss Pattersons, new lace-edged muslin aprons, was it not? Whereas the Earl of Sleyven, or so Mr Lumley assures me, is rich as a h’egg.” She eyed her blandly.

Polly gulped. “Rich as a— Aunty Midge, even Mr Lumley cannot have said that of the Earl!”

“Certainly he did,” repeated Midge with satisfaction. “Rich as a h’egg.”

“Wuh-well, even if he did,” said Polly in a wobbly voice, “I am persuaded you should not say it, Aunty Midge.”

“No; it is the sort of thing I was used to enjoin you not to say, in your early youth.”

“Yes, exactly!” replied the junior Miss Burden smartly.

“Goodness,” discovered Miss Burden. “What a curmudgeon of an aunt I was, to be sure!”

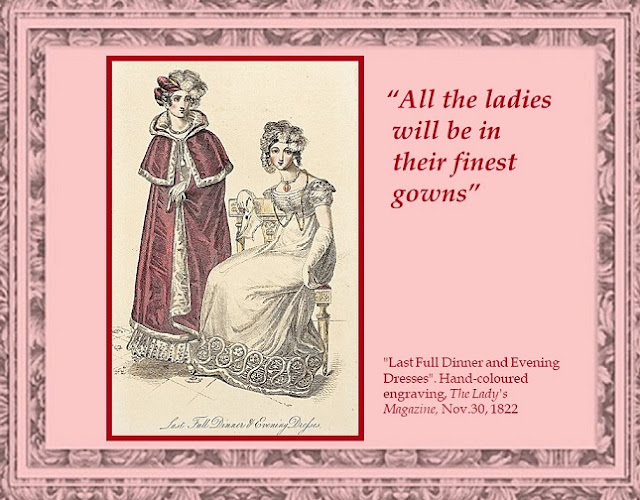

Polly collapsed in giggles. “No, but seriously, dear Aunty Midge,” she said, when she was over them, “you cannot wear that old brown silk to dinner with an earl. All the ladies will be in their finest gowns, you must see that!”

“If I do not wear it then I cannot go, Polly, dear. Besides, do not flatter yourself with the notion that we shall be placed anywhere near the Earl. In the case you had imagined that the dinner will be in that pleasant but somewhat cramped dining-room of Nettlefold Hall, you may think again. I saw Lady Ventnor’s Mrs Little in Upper Nettlefold yesterday, and she was saying that the household has been hard at it setting up tables in the ballroom for the past se’en-night. Not that it is a large ballroom, as such things go,” she added with a twinkle, “but it will certainly hold a few more diners than will the dining-room proper.”

“It is scarcely a ballroom at all, merely a large drawing-room!” said Polly crossly.

“Quite.”

After a moment Polly said in a small voice “Tables, Aunty Midge?”

“Plural: yes. I must own that my instant thought was, that in that case we shall be at the lowest table of all, barely able even to catch a glimpse of Lord Sleyven.”

“Yes,” said her niece in a small voice.

“In which case,” said Miss Burden with a twinkle, recalling her niece to the initial subject of the conversation: “my old brown silk will not matter.”

“It will matter,” said Polly with a pout, “because it is hideous!”

Miss Burden went rather red. “At my age, that can scarcely signify.”

“It does: you are still pretty! And Amanda says that Dean Golightly’s sons will be there! And in the case you do not know, or more like, will claim you do not know, Amanda says—”

Miss Burden sighed, but let her get through it.

“Weil?” demanded Polly crossly.

“The sons of an eminent clergyman, in especial if they be these sensible men of turned thirty you describe, should be above taking brown silk at its face value.”

“That is not funny, Aunty Midge, and I know you are very clever and read all those hard books of Mr Humphreys’s, but if they do not help you to—to see things, then they are of no use!”

“The utilitarian factor is not the only one, and possibly not the crucial one, if one is considering the quality of existence,” she murmured.

“Aunty Midge, stop talking nonsense! No man is capable of seeing past horrid brown silk on first acquaintance!” cried Polly loudly.

Miss Burden repressed a sigh. “Very like. But there is nothing to be done about it.”

“I concede that there is no time to do anything before the dinner party at Nettlefold Hall: no. But I shall do something about it before the Somertons’ waltzing-ball, I promise!”

“It feels more like a threat,” murmured her aunt.

Polly merely put her nose very high in the air and went out.

“You will certainly knock all the local ladies’ eyes out in that, tonight,” said Mr Patterson with some satisfaction, at the sight of his wife in a very dark blue taffety, cut very low about the bosom. Which could certainly support the style.

“Rubbish, Percival,” said Mrs Patterson, bridling pleasedly.

Mr Patterson grinned, and since the girls were not yet down, allowed himself the liberty of dropping a kiss on his wife’s large, pale shoulder.

“Really!” said Mrs Patterson, her colour somewhat heightened.

“The matching thing on the head’s good, too,” he acknowledged.

“It is a spray of ostrich tips,” she said with a sigh. “As I think you cannot but be aware. Fastened with the diamond and sapphire clip.”

“Mm. –Was there not some notion of handing the sapphire set on to Rosalind?” he said hazily.

“My dear, that was when she was born!”—Mr Patterson looked puzzled.—“She cannot wear blue,” said his wife heavily.

“Oh.”

“I have given her dear Cousin Maude’s garnet set.”

“Good. –And?”

Mrs Patterson sighed. “She can support the colour, as far the complexion goes, I grant.”

“But?”

“She has not the presence for those shades.”

Neither of Mr Patterson’s daughters had anything approaching presence: he was of the opinion that it had something to do with their having been regularly sat upon by their large, domineering mamma all the days of their lives. “Mm,” he murmured.

“Neither of them has presence!” added Mrs Patterson irritably.

Mr Patterson jumped. “Er—no, not much, Winifred,” he murmured.

“Which is why they did not take, in London,” she said, frowning. “London society is too large and busy for them. We shall see whether they will not do better in a quiet rural setting.”

—With an unmarried earl in the offing: quite, thought Mr Patterson, not saying it.

When Charlotte and Rosalind did come down he saw with a certain resignation that, though his younger daughter’s soft brown curls and creamy skin supported the garnet set well enough, Winifred had seen fit to dress her in a white gown, which in spite of its garnet-red ribbons would have been more nearly suited to a Miss in her first Season. Miss Patterson was in pink, with her Grandmamma Patterson’s pearls. She was a young woman of a quietly dignified cast of countenance: her soft, crimped brown locks were a shade lighter than her sister’s and she had her Mamma’s thick white skin—without, however, having also inherited the shoulders. Pink was by far too frivolous a shade for her, but— Oh, well. Sleyven had not looked twice at either of ’em, muslin aprons edged with Valenciennes or not, at the damned al fresco breakfast: no reason he should do so at damned Ventnor’s dinner.

Miss Somerton’s thin, bright, rather crooked little face with its sparkling dark eyes under its mop of tight little black ringlets did not look well above the insipid white muslins considered suitable for a débutante. Mrs Somerton had thought the matter over for some time, and had decided that since, imprimis, Nettlefold Hall was scarcely Almack’s Assembly Rooms, secundus, Lacey had been more or less out for a year, and tertius, those Patterson girls would undoubtedly be dressed, if not positively exquisitely then with no expense spared, her daughter should not be condemned to a shade that, frankly, made her look as yellow as a Chinee. So Miss Somerton was in a misty apricot gauze over a satin petticoat of a rather darker, more tan shade: the which combination gave the entirely satisfactory result of softening her rather angular little figure. The satin ribbons were of the darker shade and she was permitted for the very first time to wear the necklace of the topaz set which Grandmother Somerton had given her on her seventeenth birthday. And whatever their mother had seen fit to drape those girls from the vicarage in tonight—and Mrs Somerton was positive it would be suited neither to their ages nor their station in life—she was quite, quite sure that dear Lacey would outshine them all!

Mr Somerton was not yet over his defeat in re the waltzing-ball. So he merely looked grudgingly when invited to admire his daughter, and said: “Fine as fivepence, aye, and how much will that set me back, may I ask?”

“No, you may not, Mr Somerton, and kindly refrain from such vulgarities in front of Lacey,” said his wife promptly. “I am happy to say that whatever may be the case with other houses in the neighbourhood, we do not have to let such considerations weigh with us, at Plumbways.”

This was perfectly true and—vulgar though the thought might have been—Mr Somerton was not above being reminded of his comfortable position in life from time to time. He merely grunted in reply, but he looked considerably mollified.

“I hope you don’t think that’s a Mathematical, Jarvis!” said the Colonel with a chuckle as his host was discovered before the fireplace in the small salon, dubiously examining his neckcloth in the mirror over the mantel.

“No, I don’t pretend to rise to those heights. I’d be satisfied if it were merely an Acceptable.”

Choking, the Colonel said: “It is pretty bad, old boy! You should never have let Hutton go.”

“He had spoken for so long of the farm on Jersey that when it turned out not to be a chimaera I felt it would be most unfair to attempt to—er—lure him away from it. In any case, he could not tie a Mathematical, either.”

“No, but he could certainly tie an Acceptable!” said the Colonel, laughing. “Leave it, Jarvis, it will have to do, you will only make it worse by fiddlin’ with it!”

“Mm.” The Earl desisted, and turned away from the mirror with a resigned look.

“Old Ventnor has promised us a splendid dinner!” Charles reminded him, rubbing his hands and grinning. The gentlemen had encountered Sir William out riding. He had appeared thrilled to meet a friend of the Earl’s and had immediately extended the dinner invitation to include Colonel Langford.

“Peacocks’ tongues, no doubt,” returned the Earl acidly.

“Very fun—ny. Talkin’ of which, what is that, in that apology for a neckcloth, Jarvis?” he gasped.

The Earl had been fiddling with the neckcloth again. He stopped hastily. “Mm?”

“That—that thing your fiddling has just revealed,” croaked the Colonel. “It is more nearly suited to a nawab’s turban than an English gentleman’s neckcloth at a quiet country dinner!”

“Oh—this,” he said glumly. It was a large black pearl mounted on an elaborately chased gold stick. “Bates—er—forced it upon me. Well, he assures me it has been in the family forever. It was previously worn as a cravat pin by the holder of the title.”

“Aye, in the last century, maybe!” he said with feeling.

“My cousin is said to have worn it regularly,” he said glumly.

“Rubbish, Jarvis, I will lay a monkey the fellow never wore it in his life! That is just the sort of thing these old family retainers will say to a new man, y’know!”

The Earl’s long fingers hovered over it uncertainly. “I don’t feel I can take it out, now.”

“Noblesse oblige,” recognized the Colonel, closing his eyes for a moment. “Come here, and stand still!”

Smiling a little, Jarvis came and allowed him to hide the worst of the pearl pin under a fold of the neckcloth.

“And don’t fiddle with it!” said his friend sternly. “—I won’t ask where you had that rag you have put upon your back, for it has ‘Mookerjee of Calcutta’ writ all over it!”

“I had the best advice, and called in on a Mr Schultz when I was in London, before I came down here,” he said heavily. “I ordered a new riding coat and a damned evening suit, but it has not come yet.”

“That is horridly evident, dear boy; and whose was the ‘best advice’, if I may ask?”

“Barney Hartlepool’s. –Well, dammit, Charles,” he said loudly as the Colonel’s eyes bulged: “he said his father patronises this Schultz fellow, and General Hartlepool is not half a nob!”

“Friend of Wellington’s—quite,” he said, wincing, and closing his eyes.

“Then what is wrong with my patronising his tailor, pray?”

“Don’t be icy with me, Jarvis: I have known you since Harrow. One is marked as a military man by patronising Schultz, that is what.”

“Oh, is that all? Well, I am a military man,” he said, unmoved.

The Colonel groaned, and gave him up as a bad job.

Mrs Cartwright lowered her lorgnette. “A gentleman-like appearance, yes,” she concluded.

“Yes,” said Mrs Burden faintly, trying not to look in the direction of where Midge was talking to young Mr Golightly and a cousin who was apparently staying at the Deanery. The last time she had risked a glance the two young gentlemen had had very puzzled expressions and Midge was wearing that horridly bland look she did when she was being most provoking. “—I’m sorry, what was that, dear Mrs Cartwright?”

“Lord Sleyven. Most gentlemanlike.”

“Er—yes.” Mrs Burden could not see him very well from their obscure position against the wall in an obscure corner of Lady Ventnor’s crowded drawing-room, and he had not, as yet, been introduced to their obscure party; and on the whole it seemed highly likely that dinner would be announced before Sir William could bring him this way. Lettice, to say truth, did not know whether to be glad or sorry: for if Midge rejoined them, and Sir William did bring the Earl over, it was more than likely that her sister-in-law, in the humour she was in, would say something that would shock him. Well, at the least, for he would probably not have the wit to see it was shocking, something incomprehensible.

For Midge was being so exasperating tonight! At first she had said nothing, when, upon their finding a seat by Mrs Cartwright, that majestic lady had immediately pointed out the Earl. Then, when Mrs Burden and Polly had finished their polite expressions of interest—well, he was manifestly fifty, report had not lied in that regard, and very bald indeed, and, alas, as dearest Midge had predicted, what seemed an age back, yellow as veritable Chinee—when the two of them had said all that politely could be said, there had been a horrid pause, and Mrs Burden had had to say: “What do you think, Midge, dear?”

And Midge had said in a very hard, odd sort of voice indeed: “I shall have to tell Mr Lumley. Not only is he rich as a h’egg, he is also bald as a h’egg.”

Polly had gulped, Lettice had bitten her lip, and the majestic Mrs Cartwright had replied on a dry note: “I dare say he may be, but he is also one of the wealthiest men in England and a great catch.”

Lettice Burden had held her breath and prayed that Midgey would not say something truly dreadful, along the lines of then Mrs Cartwright had best set her cap for him. But Midge had only said: “True.”

Polly and her mother had exchanged nervous glances and broken into babbling social nothings.

... “I knew it would be like this,” said Polly with a sigh.

Lacey also sighed. “I did not think it would be this bad.”

“Thank you!” she said with a giggle.

Lacey also giggled, squeezed her hand, and said: “I did not mean that, silly one!”

The two young ladies were placed next each other at dinner. Lady Ventnor had apparently run out of gentlemen for the lowest table. There were in fact only two tables in the erstwhile ballroom of Nettlefold Hall, but that did not mean that Lacey and Polly were not placed at the very most obscurest spot of the second one.

Lacey drank soup hungrily, though with due precautions as to the apricot gown, but after a little said in a lowered voice: “I think we are rather better off than your Aunt Midge, however.”

Polly winced, and nodded. Miss Burden was wedged between the substantial form of Mr Gordon Shipwright, famed in the neighbourhood of Lower and Upper Nettlefold for taking no interest in anything but his dinner, unless it were the port he consumed after it, and Lady Ventnor’s Uncle Wardle, a remarkably thin old gentleman of, at a conservative estimate, seventy-five years of age, who was interested in nothing but snuff. Indeed, he appeared to talking to Miss Burden about snuff at this very instant, thus sparing Miss Waldgrave, on his other side.

... “Do you hunt, Lord Sleyven?” inquired Mrs Patterson politely.

After due consideration, Lady Ventnor had not placed the Earl next to his own cousin: that might have looked odd. Lady Judith Golightly was at Sir William’s right hand. The Earl, of course, was at his hostess’s right, and Mrs Patterson, who was certainly the most ladylike and almost certainly the best connected of the remaining lady guests, was at his right. Lady Ventnor’s table had been hastily readjusted so as to fit in Colonel Langford, the Earl’s friend, at her left. Charles glanced interestedly across to see what Jarvis would reply.

The Earl said evenly: “On occasion, yes, Mrs Patterson.”

Mrs Patterson returned a conventional reply to the effect that her husband often got out with the local hunt...

Charles looked back at his plate again, with something of a wry feeling. Well, Mrs P. had the type of bosom old Jarvis had always admired, but wouldn’t you think their hostess could at least have dredged up something passable, unmarried, and under forty for him? Or, given that all things were not possible in an imperfect world, passable and under forty? Poor old devil: noblesse oblige, indeed!

... “Personally, I am of the opinion that nothing is so truly elegant as a white soup!” sighed Miss Amanda Waldgrave. Amanda was immensely buoyed up by having been placed at the high table, next to the Golightlys’ cousin, Mr Hargreaves! Mathematics had never been Miss Amanda’s strong point, but perhaps her conclusions were not altogether inaccurate: in strict order of precedence, Miss Waldgrave should have got the seat. But Lady Ventnor had decided that never mind that, it was better to inflict the bows and the sighing circumlocutions, at least accompanied by a pretty face, on Mr Hargreaves, as to the right, and Sir William’s younger nephew, Harry Pryce-Cavell, as to the left, than the prunes and prisms and general aura of disapproval that clung to Miss Waldgrave.

“M’mother maintains that your turtle soup is the most elegant,” said Mr Hargreaves with a twinkle in his nice brown eye.

“Oh, turtle soup! But of course, yes, Mr Hargreaves, your mamma is so right! The mark of a truly fine table,” sighed Miss Amanda.

Mr Hargreaves could not think of anything to say to that, so offered her the dish of fricasseed veal kidneys in a cream sauce. Disgustin’, if you asked him. He did not voice this opinion, and she took some, simpering at him.

... Seventeen, counted Alan Pryce-Cavell, opposite. By Jove, seventeen bows. Amazin’! And that was only her front view, sittin’ down. Poor old Harry: he had given it up as a bad job, and no wonder!

Harry Pryce-Cavell was finding his other neighbour equally hard going. Miss Rosalind Patterson had agreed in a small voice that Yes, it was a crowd tonight, that Yes, the room was looking remarkably spruce (Mr Harry’s phrase), and that Yes, she and her sister had been invited to the Somerton ball.

“Er—remarkable fine weather for the time of year, is it not, Miss Rosalind?” he said desperately.

“Oh, quite. You were not at Mamma’s al fresco breakfast, think?”

“No,” he said on a hopeful note. “We missed that, I’m afraid.”

“It kept fine. We were so relieved.”

Harry Pryce-Cavell waited, but that appeared to be that. Oh, Lor’.

... “I remember my father once spoke of an elderly aunt of his who used a rose-scented snuff,” said Miss Burden, smiling at the elderly Mr Wardle.

The old gentleman produced a great series of tutting noises. Scented snuff was beyond the pale, apparently; even for a lady. For a lady was capable—with application, he said sternly—of as much discrimination in the matter of snuff as a gentleman.

Miss Burden, whose eyes had unaccountably strayed in the direction of a strong, tanned profile at the head table, blinked a little, looked at the old gentleman with real interest, and said: “Indeed? I think you are the first member of the male sex whom I have ever heard admit that females may be equal to males in any sphere whatsoever, Mr Wardle: let alone one requiring a taste and discriminating palate!”

Old Mr Wardle twinkled at her. “Am I, indeed, Miss? Well, I dare swear your experience of the male sex is not so very wide, after all! Though you are right in the main: it is a popular prejudice of the hoi polloi.” He sniffed very faintly—not snuff. “And others.”

Miss Burden rolled her lips very tightly together: the old man’s glance had flitted for a moment over Lady Ventnor. “Mr Wardle, I perceive you are entirely naughty!” she hissed.

Looking entirely gratified, Mr Wardle returned: “Alas, my age prevents that, Miss Burden. But at least I have not the closed mind that all too frequently accompanies septuagenarianism—or even precedes it.”

Midge gave a delighted gurgle. “Do, pray, tell me some more about how to appreciate the varieties of snuff, Mr Wardle. And about the way in which you blend them: that sounds quite fascinating.”

Mr Wardle ate an asparagus stalk with a considering expression on his wrinkled little face. “If I am not boring you?”

“No,” said Midge simply. “I am never bored, when experts talk to me of their subject. Mr Lumley, that is one of our local farmers, is reputed to be very boring on the subject of milk, but I have never found him so. Pray do go on.”

Smiling a little, Mr Wardle went on.

... The younger Dr Golightly, one of those sensible men of above thirty years of age whom Miss Amanda Waldgrave had described to Miss Polly Burden, had got Miss Patterson. He did not appear absolutely thrilled by the fact.

After some time Polly murmured in Lacey’s ear: “Who is the gentleman next to Miss Patterson?”

“Papa!” said Lacey, going off into a smothered fit of giggles.

Polly was rather pink. “No: the elder Miss Patterson.”

“The dark gentleman? That is Dr Golightly, Dean Golightly’s older son. Said to be as clever and serious as he is. He is also in Holy Orders, and a distinguished scholar.”

“Oh.” Polly picked at a slice of Lady Ventnor’s cook’s famous lime tart. The most delicious thing, for it managed to be both sweet and acid at the same time.

Lacey glanced at her uncertainly. “Amanda says he must be all of four and thirty.”

“Yes,” said Polly in a hard voice. She poked at the tart.

Lacey thought she saw what the matter was. “Leave it, Polly, dearest: no-one will notice,” she murmured.

Polly jumped. “What? Oh,” she said lamely, looking at the slice of tart. “Yes, perhaps I shall.”

... Miss Humphreys had got Mr Gordon Shipwright’s other, or Miss Burden-less, side. “Oh, it is the famous lime tart of Nettleford Hall! You must try it, dear Mr Shipwright!” She offered the plate.

And watched sadly and disbelievingly as Mr Shipwright took both remaining pieces of the famous tart.

... “May I help you to a little of this tart?” said Mrs Burden, at a not absolutely prominent place at the top table. Lady Ventnor had observed the new lilac silk with a positive flood of relief. Though she had had to put her there in any case: there was no-one else she could think of who was ladylike enough for Mr Golightly, and he had already got Miss Patterson on his other side. –This disposition had the effect, as she did not doubt had been noticed, of placing Charlotte Patterson with two Golightly strings to her bow. But it could not be helped.

Simon Golightly smiled at the still-pretty lady next him. “On the contrary, Mrs Burden; pray let me offer you some of this exquisite flummery.”

Shaking her head, Mrs Burden said with a tiny laugh: “No, no, you do not understand, Mr Golightly! This is the famous lime tart of Nettlefold Hall! You may absolutely not leave the table until you have tried it!”

Smiling very much, Mr Golightly took a slice.

Much further up the table Colonel Langford sat back with a little frown on his pleasant face. Why did the only woman that did not have a face like soured milk have to be placed next that imbecilic young son of Jarvis’s cousin?

... “Your mamma appeared to be getting on very well with Dr Golightly’s younger son,” said Portia Waldgrave sourly to Polly Burden as, the ladies having repaired to the drawing-room, the friends convened in a convenient corner.

“Did she?” said Polly blankly.

Miss Portia went very pink, and said no more.

“You were greatly favoured, Amanda!” said Lacey with a giggle. “Two gentlemen! And the top table!”

“Ye-es... Personally I find that very young men are not entirely of a serious disposition,” replied Miss Amanda judiciously.

“Oh, pooh, Amanda, do not be such a hypocrite!” cried Portia crossly. “You look like the cat that has been at the cream!”

“Hush!” hissed Lacey with a nervous glance across the room at her mamma. “At least none of us were condemned to snuff, like Polly’s poor aunt!”

Portia sniffed slightly. “I thought she and that old man seemed to be enjoying themselves thoroughly!”

“Er—well, yes, Aunty Midge looked... genuine,” said Polly on an uneasy note.

The Waldgrave sisters looked at her blankly.

“Genuine?” said Miss Portia.

“I incline to the opinion that you cannot possibly mean genuine, my dear Polly. Genuinely interested, possibly,” said Miss Amanda.

“Mm,” said Polly, avoiding Lacey’s eye.

Mrs Waldgrave, meanwhile, had got Miss Waldgrave into a quiet corner. “My dear Eugenia, I do think you could make a push to chat to the younger Dr Golightly and his brother, when the gentlemen return.”

“Mamma, it is scarcely my fault that I was not placed near either gentleman at dinner,” she said colourlessly.

Mrs Waldgrave flushed up very much, but being a lady, did not express her true feelings at this answer.

... “My dear Miss Burden, I have it on excellent authority,” said Mrs Cartwright in a very much lowered voice, “that old Mr Wardle was once known to be not entirely respectable.”

Miss Humphreys gasped, and held up her hands in horror.

“I think I might have guessed that,” said Midge thoughtfully. “But thank you for warning me, Mrs Cartwright. At the age he is now, however, I doubt that he can be anything but respectable. He was merely talking of snuff. –It renders him quite passionate,” she added detachedly.

“Oh, quite!” squeaked the innocent Miss Humphrey supportively, nodding very hard. “He is known to be entirely passionate about snuff!”

“Hm,” said Mrs Cartwright. “While that is true, just be sure that he does not invite you into an alcove to discuss the subject further, Miss Burden.”

... Mrs Burden chatted politely to old Mrs Hunter, old Mrs Hunter’s elderly cousins, Mrs Kinwell and Miss Platt, and the even older Mr Platt. Trying not to let it be seen she was looking round the room anxiously to make sure, not that her little daughter was behaving herself, but that her thirty-year-old sister-in-law was. Oh. Talking to Miss Humphreys. Well, that was at least commendable.

... “Now, my, dear boys,” said the hearty Sir William, beaming, and taking both nephews’ arms, “you shall talk to some pretty girls at last, hey?”

The Pryce-Cavells brightened: at last they were going to meet the little stunner with the yaller curls and that lively little dark gal what was her... friend. Their faces fell as Sir William led them up proudly to the group of Miss Rosalind Patterson, Miss Portia Waldgrave, the teeth well to the fore, and Miss Bows Waldgrave. Oh, Lor’!

... “I’d take pity on Simon,” said his mother in a low voice, nodding in his general direction, “only he has brought it on himself.”

The Earl followed the direction of her glance. “He does not appear to be suffering unduly, Cousin Judith.” –Mr Golightly had found Mrs Burden again and was laughing and chatting with her.

“Who is she, Lady Judith?” asked Colonel Langford abruptly.

Lady Judith shook her head. “I have no idea, Colonel: we were not introduced. But I do not think that she has grasped that Simon’s strategy is to get her to introduce her pretty little daughter to him!”

“Is it?” said the Colonel sourly. He bowed slightly, and walked away from them.

... “Polly, if you do not immediately cut Amanda out with that Mr Pryce-Cavell, I shall do it myself!” hissed Lacey.

“What?” said Polly dully. “Oh. Very well, then, do it.”

Mr Pryce-Cavell—indeed, both Mr Pryce-Cavells—were tall and sufficiently good-looking, with heads of splendid shiny brown curls and enormously elaborate neckcloths. The sort of thing hitherto assumed by Miss Somerton, not unnaturally, to be the beau idéal of both herself and her friend. She goggled at her.

“I am not interested,” said Polly, frowning.

“Polly, do you have the headache? Shall I fetch your mamma?” said Lacey in a low voice.

“No,” said Polly, with a lump in her throat. “I think Mamma has—has forgotten I am even here.”

Miss Somerton looked dubiously at the other side of the room. Mrs Burden’s extremely plain lilac gown was now almost hidden by the black coats and pantaloons of gentlemen. Largely clerical gentlemen. Mr Waldgrave was certainly one of them, and she could not absolutely see, but possibly both of Dean Golightly’s sons.

“Um—well, she is chatting,” she said uneasily.

“Mm,” said Polly, swallowing.

Lacey took her hand. “Come along, we’ll go and sit by your Aunt Midge, shall we?”

“Mm,” agreed Polly gratefully.

They went and joined Miss Burden and Miss Humphreys. Miss Humphreys immediately began to talk of the ladies’ gowns.

Possibly in an ideal world this immense self-sacrifice on Miss Somerton’s part would have been rewarded by Sir William’s coming over with a Pryce-Cavell or a Hargreaves or at the very least a Golightly for her. As it was not a perfect world, it wasn’t, and he didn’t.

“Well, so you have seen Lord Sleyven, at long last!” said Miss Humphreys brightly as kind Sir William’s carriage conveyed them home.

“Seen! Yes, that is the operative word!” cried Polly crossly. “If you were introduced to him, dear Miss Humphreys, it is more than we were, I am sure!”

“Dearest—” protested Mrs Burden gently.

“And Aunty Midge is right: he is bald as a h’egg!” she cried angrily.

“I would not altogether... He is quite an attractive gentleman,” murmured Mrs Burden. “Very forceful, I would say.”

‘Oh, Mamma!” protested Polly loudly. “How can you! –And you did not speak to him, either!”

“But yes, Polly dear, your Mamma is in the right of it... You are perhaps too young to see it,” murmured Miss Humphreys.

“Mrs Patterson certainly did not seem unaffected!” said Mrs Burden with a laugh in her voice.

“Letty,” retorted Midge grimly, “he could have a ring through his nose and Mrs Patterson would not appear unaffected! She has two spinster daughters to get off her hands and is convinced that her family’s connections render them eligible to be the Countess of Sleyven.”

“Oh, but dear Miss Burden, that is not at all the same thing!” cried Miss Humphreys.

“No, indeed! Could you really not see it, Midgey?” said Mrs Burden.

“No,” said Miss Burden through her teeth.

“Nor I,” said Polly defiantly. “And as for that Mr Golightly!” She gave a hard laugh.

“He was a very pleasant young man, dear,” murmured Lettice.

“Yes, whom you were monopolising! You should have heard those cats Mrs Somerton and Mrs Cartwright commenting upon it: I was put to the blush!” retorted her daughter swiftly.

“Polly! That will do!” snapped Midge.

“She is tired, I think,” murmured Mrs Burden.

“1 am not!” cried Polly, forthwith bursting into loud tears.

Her mother and aunt concluded from this outburst that not only was she overtired: she had admired Mr Golightly herself. Having no idea whatsoever that it was not he at all, pleasant though his smile and elegant though his slender figure were, who had struck Polly’s fancy, but the much older, more saturnine, less elegant and far more serious Dr Golightly.

It was certainly a far from perfect world.

“I wouldn’t say Sleyven appeared all that struck by Charlotte or Rosalind. You had best sic your sister Nettie on to him after all,” said Mr Patterson with a yawn.

“Rubbish, Percival!”

Clearly his wife had drawn the same conclusion as he. “Er—it was natural, I think,” he offered kindly, “that the Earl should spend his time in such a gathering largely chatting to the older men.’

Mrs Patterson replied grimly: “I shall hold a ball, and several dinners, of course. Intimate dinners, not—not municipal banquets!”

“Mm, it was rather like that. Er, my dear, talking of municipal dinners, we have received an invitation, if you recall—”

“No!” she snapped.

“I think Sleyven will undoubtedly be there: the theatre is named for his family, after all—”

“No,” she said grimly.

Mr Patterson shrugged, and desisted.

“Mr Golightly appears a most pleasant, gentlemanly young man,” said Mrs Patterson in a firm voice.

“Who was not unaffected by that pretty Mrs Burden: yes,” he noted.

“Nonsense. She has a grown daughter.”

“She may have several daughters—and sons. Nevertheless that young fellow was making sheep’s eyes at her.”

“Kindly do not be vulgar.”

There was a slight pause.

“The girls looked very pretty, I thought, my dear: far more ladylike in appearance than those Waldgrave Misses,” he said pacifically.

Mrs Patterson merely replied grimly: “I have a slight headache. You may sleep in your dressing-room tonight, Percival.”

Resignedly Mr Patterson went off to it.

Mrs Patterson went to sleep alone, grimly determined that Mrs Burden should not get her claws into Mr Golightly and that the Earl should notice Charlotte if she died in the attempt to make him do so. ...Strawberries were said vastly to brighten and freshen the complexion, and goodness knew Percival’s ridiculous strawberry garden that he made such a fuss over was full of the things! Yes: strawberries.

Mr Somerton was mellowed by Sir William’s port, and a decent dinner. “Enjoy yourself, my dear?” he said tolerantly to his daughter as she sipped the glass of milk and he sipped the glass of Cognac that Penny had left out for them.

“Oh, yes, Papa, it was a—a very fine occasion,” said Lacey without much enthusiasm.

“Those Pryce-Cavell boys aren’t much, y’know,” he said kindly.

Lacey went very red and burst out: “Maybe not! But I did not get the chance to find it out, for those cats Amanda and Portia Waldgrave were monopolising them!”

“Never mind, my dear: they are not having their very own ball,” he said kindly.

Lacey smiled tremulously: after all, it was very good of Papa to give her a ball. But in her heart of hearts she knew it would be a disaster: there would be no pleasant young men there at all, and if by some miracle any came, Amanda and Portia would spend the entire night monopolising them!

It was a considerable drive back to Nettleford, but the Dean’s coach was extremely well sprung. Mr Golightly and Mr Hargreaves had elected to ride: Lady Judith had not objected, it gave her the chance to speak to her husband and older son.

“What did you think of Miss Patterson, my dear Arthur?”

Dr Golightly looked at his mother with a sort of humorous resignation. “About what I thought of her the time they called, Mamma.”

“Well?”

“A conformable young woman, I suppose.”

“Really, Arthur, is that all you can say? –David!” she said sharply. “Speak to him!”

The Dean woke with a start. “Eh? What?”

“Spare him, Mamma,” said Dr Golightly with a smile. “It was a very tedious evening and he bore up very well.”

“Your Cousin Sleyven is not unintelligent,” said the Dean, blinking slightly.

“I do not deny it, David. We are not speaking of him, however, but of Arthur.”

“Eh?”

“Mamma is endeavouring to persuade me to reveal my true feelings on the subject of Miss Patterson, Papa.”

The Dean shuddered.

“Er—the one you are thinking of is possibly Miss Waldgrave, sir,” said Dr Golightly very respectfully.

“Eh? Uh—absolutely, yes!” said the Dean. “Don’t ask, Judith.”

“That will do, thank you, Dean,” she said grimly. “If you cannot contribute intelligently, you may go back to sleep.”

“It’s a bit much to expect intelligence after what I must admit was a damn’ good dinner, and an evening talking horseflesh,” he said with a yawn.

“Very well. Go to sleep,” said Lady Judith acidly.

The Dean sank his chin onto his breast and closed his eyes immediately.

“I am not satisfied, Arthur,” she warned.

“If you insist,” he said with a shrug. “Miss Patterson is a vapid, characterless little thing, with very little brain to redeem the effect of something like thirty years’ squashing by that mother of hers.”

“—Tellin’ her,” murmured the Dean.

“Be silent, David. The Pattersons are very well connected, Arthur.”

“Dear Mamma, stop trying to marry me off,” he murmured.

“It is high time you were settled, with a family. And kindly do not say you have no ambitions above a quiet life of scholarship or at the most a—a rural deanery, for it is unnatural!”

“Well, I have not.”

Lady Judith took a deep breath.

“I think that will do, Judith,” said the Dean, suddenly apparently wide awake.

Lady Judith bit her lip, but subsided.

“There were only three really pretty women there,” said the Dean thoughtfully.

“Three?” murmured his son.

“Three. Your brother was monopolising one and the second was her little daughter: did you notice her? Dear little thing, with yellow curls. White muslin. Very young.”

“Oh, was that her daughter?” said Dr Golightly in an odd tone.

“Mm.” The Dean waited for him to ask who the third one was. But he did not. “Well, don’t you want to know who the third one was?”

“No,” said Lady Judith wearily. “There was no-one else who was more than passable.”

“Hair like a copper beech and a skin—what little one could see of it—like silk and rose petals!”

“What?” croaked his son.

“It is one of his ridiculous jests: ignore him,” warned Lady Judith grimly.

“No, true!” he said with a laugh. “Sat in a corner with a couple of fusty dames all night, poor little thing. Little plump thing, dressed in the most Goddawful brown rag I ever laid eyes on.”

“I never saw anyone like that there,” said his son dubiously.

“Nor I, indeed. Ignore him,” repeated the Dean’s wife.

The Dean shrugged, and sank his chin onto his chest once more.

“Red hair?” said Lady Judith.

“Mm. Copper beech,” he rumbled.

“Rubbish.”

“Arthur has always preferred yaller hair, dare say that is why he never noticed her,” he rumbled.

“Nonsense!” she snapped.

“Father, I really do think that is enough: you are upsetting Mamma,” said Dr Golightly.

The Dean opened one eye, gave him a sardonic look, and closed it again.

Dr Golightly sank back into his corner of the carriage, biting his lip. He was aware that in spite of the manner his father often assumed, the Dean was an extremely clever and noticing man. It was possible that the story about the girl with the red hair was just a tarradiddle: but even if it were not, Arthur Golightly was in very little doubt that she had not been at all the point of his father’s remarks.

“Thank God that’s over,” said the Earl, yawning widely.

Charles leaned his head back against the upholstery of the carriage. “Jarvis, who was the lady in the lilac silk?”

“Eh? Er—I don’t think...”

“Tail and fair. She was talking to your idiot nephew, or whatever he be, when you and I were chatting to Lady Judith!” he said irritably.

“Uh—oh, yes. No, I didn’t meet her.” He yawned.

“Honestly, Jarvis, you would provoke a saint!”

“Oh,” said the Earl, sitting up and staring at him. “Thought you were a man of address, Charles?”

“I could not find anyone to whom I had been introduced who knew her,” he said tightly.

“Sad want of enterprise, there,” he drawled.

“Very funny, Jarvis,” said the Colonel heavily.

“I’m sorry. Well, she must be some local lady; dare say we’ll meet her again at any number of these occasions.”

“Mm. I dare say.”

“Uh—what was she like?”

“Too tall and too flat for you!” replied the Colonel furiously.

“Don’t be like that, dear boy,” he murmured.

“Sorry, Jarvis,” said the Colonel, biting his lip. “But that damned young Golightly was making eyes at her half the night!”

“Mm. –Is she flat?”

“Er—well, smaller than we had always had the impression you liked ’em, old man, but er—no: not flat.”

“I’m relieved to hear it,” he said politely.

Charles smiled feebly.

After a little Jarvis said slowly: “Did you notice any female there with dark red hair?”

“Um—no. Why?”

“It doesn’t matter. I just thought— I must have imagined it.” His friend said nothing and after a moment he gave an awkward laugh and added: “Possibly it is common in these parts!”

At this Colonel Langford refrained with an effort from raising his eyebrows. “Er—dark red hair as well as not flat, Jarvis?”

“Y—No! I merely caught a glimpse of red hair at the damned dinner!”

The Colonel took a deep breath. “I think I see. ‘Droit de seigneur’. Jarvis, have you made a damn’ fool of yourself?”

The Earl opened his mouth. He shut it again. “No,” he said feebly.

“You can tell me,” said the Colonel mildly. “We are all of us fallible, dear old man.”

“It was nothing,” he said tightly. “I— A country lass. She was stuck on a damned wall: she had some damned ragged parasol that had blown away. I hauled her down.”

“And?”

“Nothing. Well, I took a kiss, what natural man would not have?” he said crossly.

“Depends whether she was pretty or no.”

“She was very pretty,” he said, drawing a deep breath. “In a tight print gown that did not conceal the fact she had never heard of the corset. With—with very long, dark red hair,” he added limply. “Um—very pink cheeks.”

“Short and plump?”

“She did not look in the least like Kitty Marsh!” he shouted.

“I’m glad we’ve got that out of the way.”

The Earl bit his lip. After quite some time he said: “I’m Hellish sorry, Charles.”

“That’s all right...” he said slowly. “I see. You wanted to, but did not.”

“Of course I did not: the little thing was scared stiff!”

“Aye, and you’ve been regretting it ever since,” said Colonel Langford with a sigh.

“I— Something like that,” he said in a stifled voice. “Can we forget it? It was damned stupid.”

“Mm.”

The gentlemen lapsed into silence.

Of all the persons who had attended the Nettlefold Hall dinner only three went to bed that night in a state of unalloyed happiness. The first, perhaps needless to state, was the genial host himself. It had been a splendid do, had it not? Went off splendidly well! Lady Ventnor could not altogether agree: she had been aware that most of the persons whom Sir William had insisted on inviting had been neither to the Earl’s taste nor to that of his cousin, Lady Judith. She conceded, however, that it had gone better than she had expected, and Sir William went to sleep with a smile upon his ruddy countenance.

The second person to retire that night with sentiments of unalloyed pleasure was Miss Amanda Waldgrave. She was aware she had looked her best, she had been at the top table next two gentlemen, the gentlemen had come and spoken to her and her sister after dinner, and Mamma was pleased with her! Beside her, Miss Portia, who might have been expected to have been in a similar state, given that she had at least shared in the after-dinner conversation and that it had not been her fault that she had been placed at the lower table, stared sulkily into the dark for a long time. It was not fair! And Amanda was a vain pig! And Mrs Burden had no right to—to foist herself on young gentlemen, so: she was a widow, and nigh old enough to be his mamma!

The third attendee at the Nettlefold Hall dinner to fall asleep that night in a state of perfect content was Miss Humphreys, an innocent smile on her innocent countenance, in her narrow white bed with Tabitha Cat on the end of it. It had been so exciting! The ladies’ dresses! And the flowers! And the wonderful food! And to think she had dined with a real live Earl! Powell Humphreys, whose back had been nagging him all day, had said wearily as she tiptoed in and peeped at him: “I am not asleep. How did it go? Did you actually speak to the Earl?” His sister had replied without a trace of resentment: “Oh, no, Powell, dear, of course not. But I had the most excellent view of him, all through dinner!” Powell had said nothing more: there was, after all, no pleasure in destroying the illusions of the innocent. Who were undoubtedly the lucky ones of this far from perfect world.

Further out of the village, in the little house misnamed Bluebell Dell—it was not in a dell and had no bluebells in its garden—Lettice Burden retired with what could only have been described as mixed feelings. Midgey had been so odd all evening! Well—poor darling, that brown silk was truly dreadful. They must do something about it without delay. As for Polly—well, she was overtired, poor lambkin, she was not yet used to evening engagements. Possibly a tonic? ...Oh, dear, if there were to be many more of these engagements—and she must not refuse any invitation, for Polly’s sake—then it was not only a question of Midge’s awful brown silk, they would all speedily find themselves at a loss for suitable garments. ...That deep blue taffety of Mrs Patterson’s had been just so— Lettice wrenched her mind firmly off the topic of Mrs Patterson’s wonderful gown and endeavoured to count her blessings.

In all these musings, did she give Colonel Langford a thought? Well, no. She had been too far down the table to have noticed him. And far too polite to peer up towards her hostess and the distinguished guests next her. She would not have known him from Adam had she met him in the street the next morning. It was a far from ideal world, indeed.

Polly went to bed determined to sob her heart out: for Dr Golightly had never so much as glanced at her and there was no reason he should, for she was only an undistinguished Miss from nowhere in particular! As the Dean had noticed, her assumptions were not all correct, but there was no way, it not being a perfect world, that she could guess this. She was so tired, however, that only two tears watered the pillow before she fell sound asleep.

Midge retired silently, her round, pink-cheeked face puckered up into a horrible scowl. She might have known! No wonder he had said something about “droit de seigneur”—which, by the by, was just about the most impertinent aspect of all his impertinent conduct! It was not, of course, and the pink cheeks flamed up as they did whenever her traitorous brain worked itself round to that episode. She got into bed, scowling ferociously. What did it signify, after all, whether he was merely an unknown gentleman or—or the King of Persia! This last image did not, alas, indicate that she had given in to Mr Humphreys’s hints and taken up Horace. It was merely one of Powell Humphreys’ sayings, which she had unconsciously picked up from him.

There was a heavy thud, two seconds after she had blown her candle out: Mischief landing on the foot of the bed. He made his way up it, the purr a terrific rumble. Midge turned over hurriedly: he had the most frightful habit of planting an extremely heavy paw right in the middle of your stomach. Mischief walked over her—it could not have been said to have been climbing, he barely altered his stride—and settled as close as he could get to the stomach. The purr was deafening.

“Brute,” muttered Midge. The big old cat purred harder than ever. Miss Burden abruptly turned her face into her pillow and sobbed and sobbed.

Next chapter:

https://thepatchworkparasol.blogspot.com/2022/12/a-waltzing-ball.html

No comments:

Post a Comment